I keep forgetting how bliss ignorance was. A half-hour ago, I played Hit Em Up by Tupac Shakur and was transported back to my childhood kitchen in Brooklyn, NY. The music video just premiered, and I was excited to enjoy the drama. I was ten years old and settling into my childhood apartment after coming home from school. Flava Videos was on the television.

The tube was fitting for 1996; rectangular, sharp edges that jabbed my ribs when I reached behind to adjust the antenna, and a big ol butt in the back that my mother would touch when she got home from work to see if I was watching without permission. The TV had 12 presets, but if you opened the panel, there were 12 adjacent knobs that, when tuned just right, offered a whole world of additional local channels.

Channel 6 somehow became an occasionally grainy channel 54 with access to BCAT: Brooklyn Cable Access Television. Local entrepreneurs from Brooklyn were carving a path to bring entertainment, worship, and telemarketing to Brooklyn. I only cared about Hip-Hop. I was an impressionable young kid engulfed in a drama that I knew nothing about.

The East Coast-West Coast beef was at its peak. We didn’t have cable, but Bobby Simmons came on public access television every Monday through Friday and showed me the latest music videos.

I remember the excitement, the disrespect, the “oooh” as I raised a fist to my mouth, and the wide eyes as I watched Biggie and Lil Kim get mocked. I was living vicariously through these artists.

Can't Touch This

Hip-hop embodies and demands a braggadocio demeanor that makes you untouchable. Being untouchable is an identity young Black children crave. They also need it to exist. If you can't touch me, I've earned your respect and admiration. But once I add fly kicks, drip, and swag, it's homage based on being cool—Hip-Hop and being cool drive social culture.

The Black Experience's narrative is that Blackness is very touchable, wherever and whenever, by whoever. To counter that, Black kids live in these arrogant and braggadocio personas for safety and a sense of freedom.

Bobby Simmons, the host of Flava Videos, kept me up to date on HIp-Hop and I fed on falsified energy. It was reality tv. It wasn’t me stuck in the kitchen while my mother watched soap operas, and it wasn’t Steve Urkel annoying poor Carl Winslow and the both of them resolving their issue in a half-hour. The tension was real. I had to rep the east coast because if Pac was dissing Biggie, he was dissing the entire East Coast. That’s what I was conditioned to believe.

Sometimes the tension is fake, and sometimes it’s real. Both Biggie and Pac were murdered, so the drama spilled over into reality. Being young didn’t allow me to understand what was happening, so I assumed it was just part of Hip-Hop and the Black experience—Black people of notoriety having their fates sealed by gun violence.

Is There More?

There was more outside of the violence and glamour, though. Hip-hop offered love, passion, and friendship. Mary J. Blige and Method Man brought a fusion of styles together. Biggie and Faith taught me to forgive when it comes to love. With the help of Blackstreet, Foxy Brown created a desire for a confident and lyrically deadly woman.

I was young and just going along with social culture and what allowed me to be part of the inner circle of conversations. Although I craved adult experiences and vicariously experienced them through television, I had to accept the limitations of being young and the dangers and possibilities that came along. Being a teen offered disconnection from life responsibilities. There was still an air of mysticism and curiosity that provided hope and excitement about life in my twenties and thirties.

Today, I’m somewhat of an adult. I’m still young and hopeful enough to make an impact, but I’m also finding myself more aware of aging and responsibilities. I am responsible for myself, my family, my community(es), and this planet. I’ve inherently taken on these social and individual responsibilities. I know that my effort matters as much as yours.

I've always been hopeful about my future. But today's teens don't have that luxury; no teen ever will.

And It's Gone....

Rodney King’s beating was a blip in my childhood. Abner Louima’s assault was another. And although I still feel the social impact of those incidents, they were too far and in between for me to feel the ever-present gloom about the Black Experience. But for Generation Z, the names of Michael Brown, Breanna Taylor, George Floyd, LBGTQ+ rights, bigotry, hate, climate change, ICE, Trump, Biden, and every top trending keyword in Google search results adds pressure, nearly every day of their life.

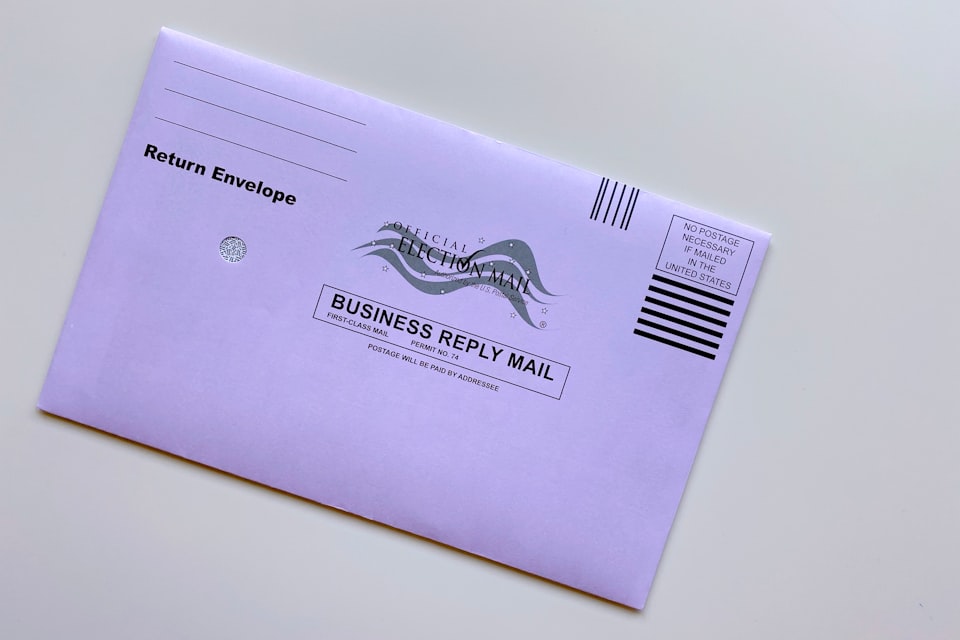

Check Google’s Top 2020 Search results for the US. It’ll show you the following:

- Election results

- Coronavirus

- Kobe Bryant

- Coronavirus update

- Coronavirus symptoms

- Zoom

- Who is winning the election

- Naya Rivera

- Chadwick Boseman

- PlayStation 5

If we place them in categories, we get:

- Anxiety about the country

- Death

- Death

- Death

- Death

- I’m only wearing underwear, and I love it

- Anxiety about the country

- Death

- Death

- Can I play in between my zoom classes/meetings today?

What’s the common theme?

Sometime between late 2009 and early 2010, I had my first panic attack. My dormant Thanatophobia showed its face as I watched the final episode of Cowboy Bebop. I've watched the series from beginning to end a few times before, but my mortality hit me that night.

Hip-hop told me I was untouchable, but for the first time in a long time, I felt fear. My soul shook while my mouth opened, ready to howl as I gasped for air. Somehow, through the lack of air, pacing back and forth, and terror of repeating, "You won't exist", I focused just enough to grab a pillow. The panicked energy had to go somewhere. I had to repress the chaos racing through my body. I didn't want my mother to hear, and I didn't want help. I was ashamed, and the braggadocio in me told me that I needed to fight this on my own.

After I grabbed my pillow, I sunk my teeth into it, ripped at the case, and tossed my head back and forth like a rabid dog until I whimpered and tears rolled down my eyes. Eventually, energy and franticness gradually flowed away. I sat on the edge of my bed, still gasping for air, eyes wide with tears rolling down my face as I wondered what was happening.

It Ain't Personal

Death has always been personal. My biological father was murdered when I was two. My godfather was murdered when I was ten. My friend's uncle was murdered a few years later. The Black Experience is awareness of death at a young age. Although I was hopeful for the future, my experiences told me that Black males don't live past their mid 20's.

In Cowboy Bebop, Spike dies at the end. But his death hit differently this time. And it hit differently because my depression, thanatophobia, nihilism, and cynical views of society had fused with my new awareness of the history and impending doom of the Black Experience.

In media, dying is as common as drinking a cup of coffee. A six-year-old shouldn't have that direct connection with death through gun violence. Most of my childhood friends had a biological parent who was dead also or who wasn't around. We never talked about it. A friend's father was in prison for murdering his wife. We never talked about it. Young people shouldn't have to deal with that. But we did, and it never seemed like an issue at the time because we were kids, and Hip-hop was our escape from the pain. Being ignorant of our real world and focusing on the fantasy of rap beef on television allowed us to stay young.

There's no escaping reality anymore. Content on the internet is geared toward taking up responsibility now. The kids are ill-prepared and doomed.

Part 2 Coming May 15th (Available to Subscribers Only)